Is Your Child on The Feast or Famine Cycle? (And why it’s important to find out!)

By Jean Antonello, RN, BSN, obesity and eating disorders specialist and author of The Great Big Diet Lie, How to Become Naturally Thin® by Eating More, Breaking Out of Food Jail and Naturally Thin® Kids, www.naturally-thin.com

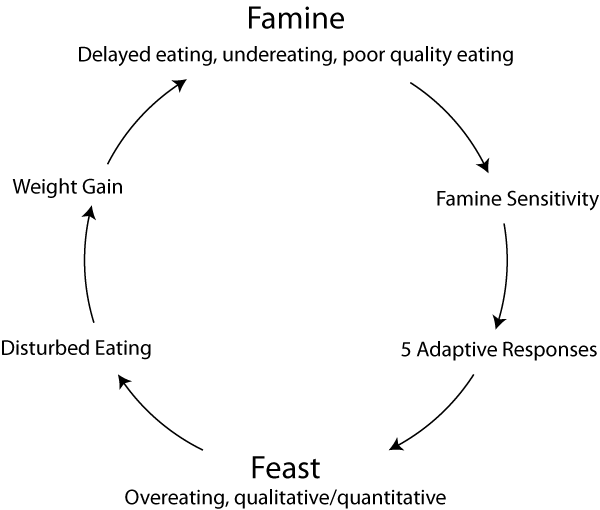

Kids of all ages (and their parents) can easily become trapped in a pattern of eating I call the Feast or Famine Cycle. Because we live in such a hurry-up culture, we all eat on the run, miss meals at times, eat poor quality food and sometimes don’t eat enough good food. This seems ironic in a country where obesity is so prevalent, but actually, there is a relationship between reckless eating and weight gain. This relationship is best understood by looking at The Feast or Famine Cycle. This pattern helps us discover and troubleshoot areas that can throw kids’ healthy eating behavior off track. This cycle also demonstrates ways in which going hungry contributes to weight gain and disturbed eating in famine- sensitive kids. Be alert to these symptoms before weight or eating problems develop too far.

Here is the diagram of the cycle:

Symptoms of the Feast or Famine Cycle

The two most obvious hallmarks of the Feast or Famine Cycle are:

- triggers: delayed eating, under eating, poor-quality eating (famines)

- symptoms: overeating, qualitatively and/or quantitatively (feasts)

We will look at the famine phase of the cycle first because that’s the starting point of all the adaptive responses (symptoms) that follow. The feasting is simply a result of delayed eating, under eating, and/or poor quality eating. And the feasting can take on several characteristics.

The famine phase of the feast or famine cycle

The Feast or Famine Cycle always begins with a famine, or some type of under eating.

All kids go hungry once in a while. This is unavoidable, and it usually lasts a relatively short time. But this is not the famine that starts the cycle. A true famine is a longer time when a child is hungry and consciously or unconsciously goes without food. Occasional famines are normal, but regular famines force kids’ bodies to adapt.

Famines provoke these five adaptive responses: increased appetite, decreased metabolic rate, cravings for sweets and fatty foods, preoccupation with food and eating, and avoidance of physical activity.

The degree to which an individual child is affected by a famine—how strong these five adaptive responses are—depends very much on his or her genetics. All kids inherit specific traits or sensitivities from their parents, and the potential to adapt to famines is no exception. I use the term famine sensitivity to explain the differences in the ways kids’ unique bodies respond to regular famines.

Some kids rarely suffer any cravings or excessive hunger, even though they go hungry at times, perhaps often. These kids are not very famine sensitive. They tend to be thin. Because they don’t tolerate hunger well, they might be rather demanding when they get hungry. But, they may also be good at ignoring their hunger when they must and eating well when they get an opportunity.

Other kids don’t fare as well with unsatisfied hunger. They may or may not tolerate hunger well, but their eating behavior is definitely affected by famines, sometimes dramatically. Following a famine experience or a series of regular famines, they experience powerful hunger pangs that demand bigger than normal meals. They also crave rich, sweet foods and think more about eating than others do. They may feel lazy and unmotivated after experiencing a famine and eventually feel tired in general.

These kids are very famine sensitive. They tend to gain weight easily and get a reputation for eating a lot. They never see going hungry or delayed eating as part of their problem. And their parents don’t either. But it is. In fact, it’s the trigger for all the struggles that follow.

Most kids are somewhere in between these two extremes. Moderate famine sensitivity means just that: Kids’ bodies react to going hungry with moderate symptoms. I’ll discuss how to evaluate your child’s famine sensitivity in an upcoming article.

The first thing to do to help understand your child’s vulnerability to weight or eating problems is to consider the role that ignoring hunger plays in the Feast or Famine Cycle and the five adaptive responses. This will help you identify potential trouble spots to avoid as your kids move into different stages of growing up.

Once a pattern of under eating or poor quality eating is established, kids with famine sensitivity will experience some degree of compensatory feasting. This allows their bodies to make up for lost calories in order to maintain their weight and ensure continued growth. The additional calories also provide excess fat for protection in future famines.

Bodies that don’t get enough fuel on a regular basis may store fuel in the form of fat to ensure survival through these feasting adaptations. Individual bodies learn from the food supplied or lacking, whether or not there is danger of famines in the future.

The feasting phase

Kids’ bodies accomplish feasting by:

1. taking in more calories by:

a) eating more food

b) eating calorie-condensed foods

2. conserving energy

Several key adjustments happen in order for kids’ bodies to take in more than the normal amount of calories. First, they become insensitive to their natural eating instincts, losing touch with their normal appetite signals and fuel-full signals. This allows them to overeat and do make-up eating following regular famine experiences. Second, they also conserve energy by lowering their overall metabolic rates and resisting physical activity.

Taking in more calories

Kids lose touch with their hunger and fullness

The most significant consequence of feast or famine eating patterns is that kids lose touch with their natural appetite signals, the ones they were born with. Under eating, delayed eating, and poor-quality eating force kids’ bodies out of natural eating rhythms. Normal hunger is replaced by excessive hunger, and fuel-full signals become indistinct. So kids are more likely to overeat, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Children and adolescents who famine regularly often report that they are always hungry or never hungry. These are their bodies’ adaptations to an insecure food supply.

It may appear that their bodies are defective and need more external dietary control, but this is not true. Kids who experience this loss of “body-controlled eating” inadvertently force their bodies to adapt to famines, creating a great danger of developing weight and eating problems that may last a lifetime.

Whether kids go hungry deliberately or accidentally makes no difference to their bodies’ adaptive mechanisms. Going hungry simply requires a detachment from body signals that at one time kids were all perfectly in touch with. When children or teens lose touch with their immediate need for food, other natural fuel signals become indistinct in response. For example, in order to accommodate feasting (taking in excessive calories in make-up eating), kids must develop the ability to tolerate overeating. Overeating is normally an uncomfortable experience that kids naturally avoid by stopping when they feel full.

Eleven-year-old Tommy isn’t hungry for breakfast and rarely eats even a piece of toast before school. Although he may be mildly hungry by noon, the school lunches are so unappealing that he eats little of the food on his tray. At five o’clock when his mother picks him up from the neighbor’s, Tommy is so famished that he bee-lines it to the refrigerator. Defying his mother’s protests, he eats ice cream bars and leftover pizza. In spite of this binge-type snacking, Tommy eats the spaghetti dinner his mother prepares, with lots of garlic bread, as well as a brownie and ice cream dessert.

Rather than becoming a source of discomfort (standard equipment for all human beings), overeating feels comfortable and normal to kids who lose touch with their hunger signals. And as they tolerate both intense hunger signals and overfull signals, the Feast or Famine Cycle takes a firm hold. This is how kids get overweight and develop troubled eating behaviors.

Kids overeat (make-up eating)

The second and most obvious way for a body to catch up after inadequate food intake is to consume more food–qualitatively and quantitatively. Kids who overeat, binge, or do make-up eating not only eat more food, they tend to eat foods with more calories per bite. These richer, calorie-dense foods are the ones they crave when they have had to go hungry.

Madison, a nine-year-old, has fallen into the habit recently of eating an entire box of cookies as soon as she gets home from school. Her mother hides the cookies and puts fruit out on the counter in hopes that Madison will eat something healthier, but the little girl finds ice cream or the evening’s dessert to eat instead. Upon questioning, Madison’s mother finds that her daughter is not eating the school lunch because of a scheduling error that allows Madison only ten minutes in the lunchroom. Madison can hardly get through the line in that time. The real problem isn’t Madison’s bingeing on sweets. It’s the daily famine she’s experiencing at school.

Preoccupation with food is the setup for overeating, an important symptom to watch for in children. Talking often about eating, or an overemphasis on eating special, favorite treats, and the like, sometimes signal hidden famines in a kid’s life.

Conserving calories

Besides increasing caloric intake through overeating, kids’ bodies adapt to regular famines by burning less fuel in two ways:

- slowing metabolic rate

- Avoiding physical activity

Going hungry causes kids’ metabolic rates to slow down. The more regular and more serious the famines are, the more significant this adaptive effect. Of course, genetic differences also play a role, but this adaptive response is universal. Kids who go hungry need to burn energy more slowly than kids who are eating plenty of great food regularly throughout the day. Unsure of the food supply, their bodies spend limited energy more sparingly.

Possibly as a result of this drop in metabolism, kids in famine mode experience physical depression. They adapt by avoiding physical activity. Again, the uncertain food supply causes these bodies to hold onto their fuel and spend it sparingly.

Many parents, physicians, and therapists believe that under activity is the fundamental problem in overweight kids. Without looking at kids’ terrible eating patterns, these parents try to get these kids moving more. But they are defeated before they begin. It’s a dead-end road. The avoidance of physical activity in the child who goes hungry is only an adaptive symptom. To treat the symptom, rather than its cause, makes as much sense as giving oxygen to a person having difficulty breathing because his necktie is too tight.

Although the reluctance to be active in kids who experience famine is not psychological, a true depression can occur in kids who often go hungry. Lack of motivation, negative attitude, avoidance of challenge, moodiness, and many other manifestations of depression may be seen in kids suffering this effect. Probably a significant number of kids on antidepressant drugs are being treated for symptoms that could be relieved or at least improved by adjusting their food availability and eating schedules.

Is your kid on the Feast or Famine Cycle? Look for these symptoms:

- regular overeating and/or bingeing

- preoccupation with food or eating

- frequent requests/preferences for sweets or high fat foods eating from boredom, restlessness, especially at night

- eating in response to emotional upset or stress

- significant overeating on special occasions

- worries about appetite or eating behavior

- excessive hunger or symptoms of low blood sugar (headache, faintness, irritability, anxiety, confusion, feeling desperate when hungry)

Maybe you’ve noticed these symptoms before but didn’t know what to make of them. Now you do. You’re learning what to do about them. If your kids don’t have any of these symptoms, thank heaven for that, and know that you can learn how to protect them from the nightmare that this adaptive cycle brings.

Posted in Articles